Our Questions

At SNAPlab, we are driven by fundamental questions about how the auditory system enables us to listen and communicate in complex, noisy environments such as bustling streets, crowded restaurants, and lively sports venues—an extraordinary ability that machines have yet to fully replicate. You can explore our related work in detail on the Publications page.

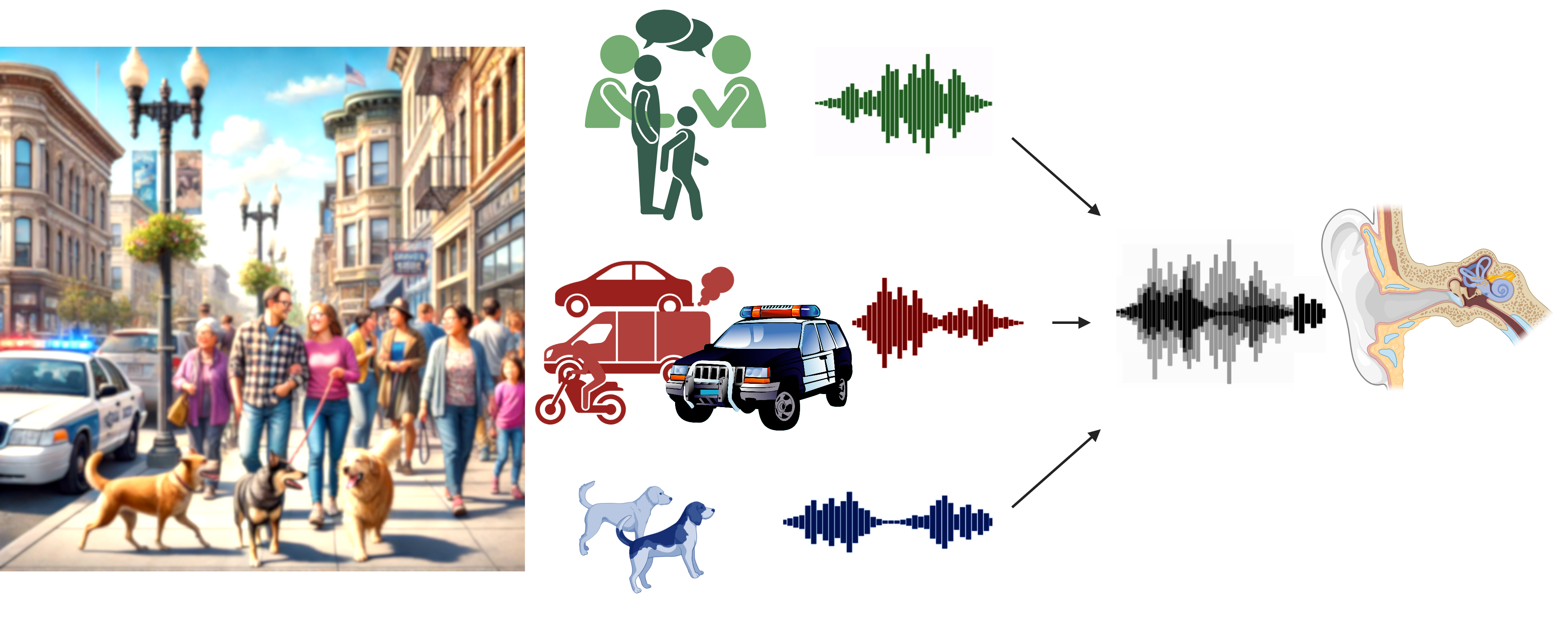

Imagine having a conversation with a friend across the table in a noisy restaurant—a task that many perform effortlessly. Now, replace yourself with your smartphone’s voice assistant. How successful do you think it would be in the same scenario? To understand why this is so challenging, consider an analogy proposed by Albert Bregman, a pioneer in auditory scene analysis: Imagine standing on the shore of a lake, blindfolded, with your ears plugged. You place one or two fingers into the water and feel only the ripple patterns hitting your skin. From this limited input, you are expected to infer the number of boats in the water and their activities—a seemingly insurmountable task. Yet, this is exactly what the auditory system accomplishes when it decodes pressure ripples in the air (sound waves) to analyze and interpret highly complex sound environments. At SNAPlab, we strive to uncover the mechanisms by which the auditory system is able to encode and analyze the sound information in such "cocktail-party" environments.

In addition to investigating the basic mechanisms that support successful cocktail party hearing, a prominent focus of our lab is in understanding how these same processes are altered by various forms of sensorineural hearing loss.

Beyond Audibility—Understanding "Suprathreshold" Hearing Challenges

Hearing loss negatively impacts communication and quality of life for one in six individuals worldwide, with global estimated costs approaching a trillion dollars. It is well known that hearing loss decreases one's ability to perceive soft sounds—a loss of audibility. Accordingly, current best practices for clinical evaluation and management focus on measuring hearing sensitivity (i.e., the softest sounds one can hear) and restoring audibility through hearing-aid amplification. Yet, despite using clinically prescribed, state-of-the-art hearing aids to restore audibility, patients with sensorineural hearing loss often struggle to understand speech in "cocktail-party" environments such as crowded restaurants and busy streets. This difficulty—being able to hear sounds but unable to pick out and understand speech amidst background noise—leads many to even abandon their devices. Indeed, it has been recognized for some time in the literature that speech-in-noise performance in individuals with sensorineural hearing loss lags substantially behind that of those with clinically normal hearing, even when amplification is provided. Yet the mechanisms of is these deficits are not well understood. A key goal pursued in our lab is to characterize how hearing loss alters suprathreshold sound encoding—that is, the neural representation of audible sounds—and how it affects the brain mechanisms of auditory scene analysis.

Furthermore, cocktail-party hearing is challenging not only for patients with hearing loss, but can also be challenging for individuals with autism, older individuals, and those with mild traumatic brain injuries (concussions). Indeed, even among young and middle-aged individuals without clinical hearing loss, we have shown that large differences exist in the ability to perceive subtle features of sounds and to listen in multisource environments.

Understanding the mechanisms contributing to hearing difficulties and individual differences in cocktail-party listening is paramount for developing targeted, personalized treatments.Characterizing cochlear deafferentation and "central" auditory plasticity associated with aging and acoustic overexposure

It has been conventionally recognized that aging and exessive exposure to intense sounds can each contribute to overt clinically measureable sensorineural hearing loss. More recently, there is evidence from a range of animal studies and from our previous cross-species work, that normal aging and overexposure to intense sounds could alter the physiology of the auditory system even when not inducing clinical hearing loss. Specifically, aging and acoustic overexposure can induce damage to cochlear afferent nerve endings without damaging cochlear sensory cells (i.e., hair cells). This can in turn unleash brain adaptations (i.e., changes in the central auditory system) that may negatively impact how we listen in complex environments. A current focus of our lab is to characterize these changes systematically from the cochlea to the cortex and how it affects one's listening ability in complex multisource environments.

How do we selectively listen to one source of sound in a crowd while ignoring others?

Our ability to selectively attend to the sound source of interest in a mixture and ignore other sounds is well known but not well understood. For the same sound mixture, a listener with healthy hearing can choose which of the diffferent sources in the mixture they listen to. At SNAPlab, we study the neural mechanisms that support such auditory selective attention and how they interact with hearing loss and the fidelity of neural coding of sound mixtures by the ascending portions of the audditory system.

Translational Goals

Though we often engage in basic scientific research, the overarching goal is to help translate the knowledge to effective clinical and engineering tools. The basic questions asked, and the non-invasive measurement techniques used, naturally lend themselves to translational research towards:

- Biomarkers for the diagnosis and (importantly) stratification of listening problems owing to diverse causes,

- Devices to assist patients with hearing difficulties,

- Decoding brain signals for brain-computer interfaces (BCI), and

- Mimicking biological auditory computations in machines for various technological applications.

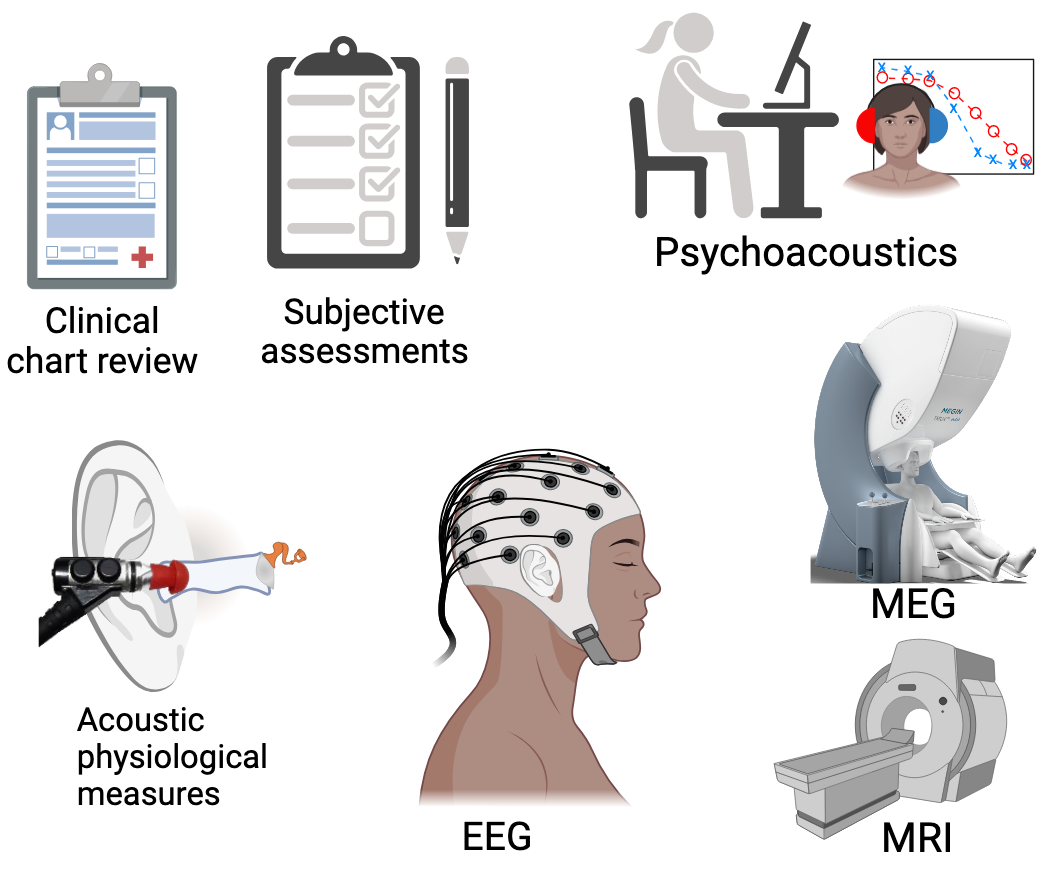

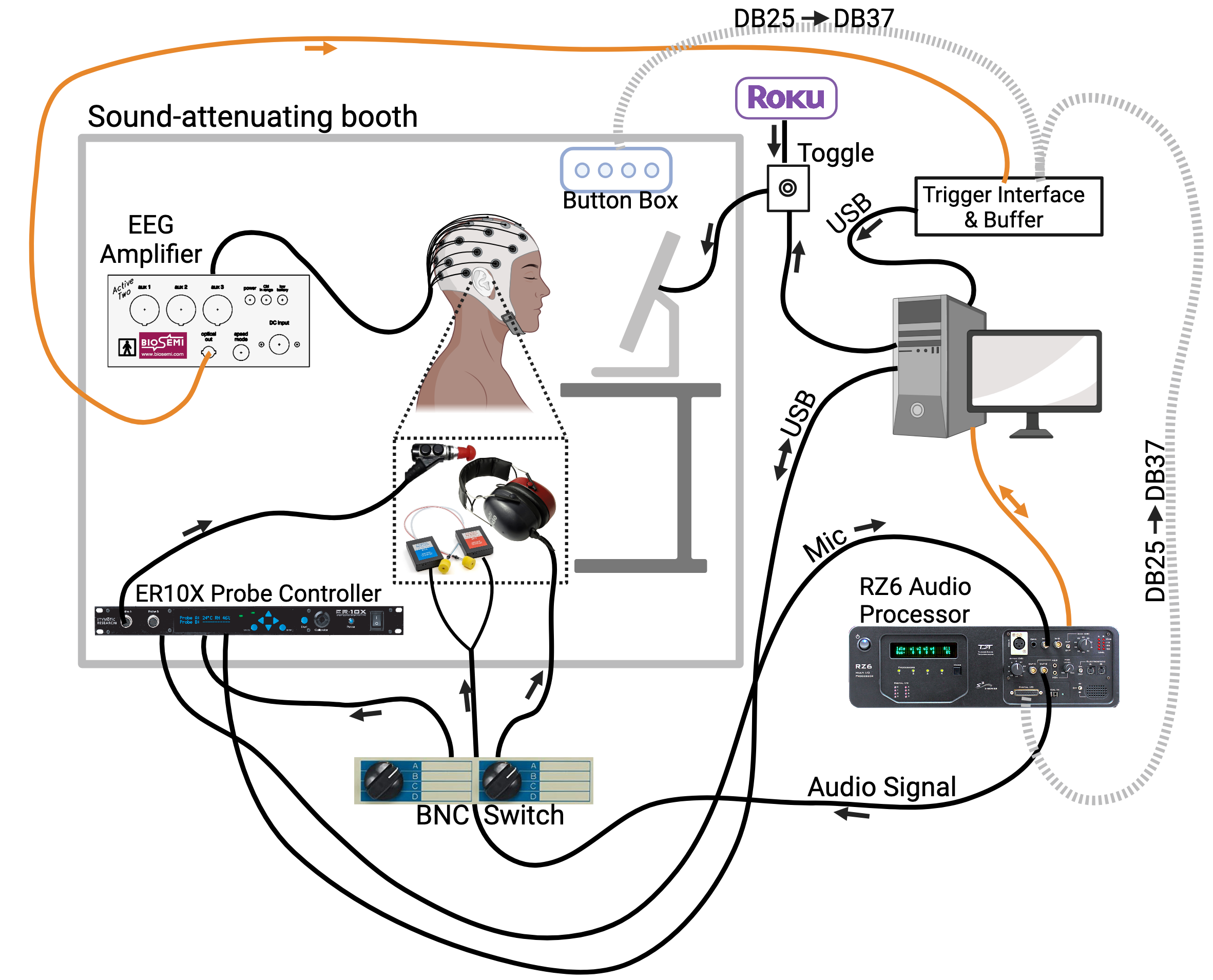

Techniques

The complexity of the neural computations that underlie auditory perception demands a detailed multidisciplinary approach to its study. Thus we employ several approaches in conjunction with each other. Given that the phenomenon we are interested in studying is human perception, we conduct experiments to understand the relationship between sound information and the corresponding percept, under different behavioral task conditions (a.k.a. Psychoacoustics). To probe the neural mechanisms that support such perceptual outcomes, we use a range of human neuroimaging and electrophysiological techniques to directly measure physiological responses to sound. We analyze these responses using signal processing, statistics, and machine learning approaches. The knowledge gained from psychoacoustics and objective physiological measures is then integrated into computational models of audition, which then inform the next set of experiments. We also take advantage of the large and vibrant hearing-research and clinical communities in Pittsburgh through active collaborations.